No. 83 - An interview with creativity guide Jill Margo

"Making things and embracing joy are acts of resistance with profound power"

As long-time readers will know, Jill gets mentioned a lot here at Feed the Monster because I’ve benefited so many times from her wise counsel on maintaining and nurturing a creative practice. Jill is a creativity guide who “helps creators to cultivate and sustain nourishing, liberatory creative practices, with compassion and purpose, and in tune with natural rhythms”. She’s also a phenomenal writer, an editor, and a pressed-flower artist. As I wrote in my last post, I really could have used Jill’s services thirty years ago when I was battling every artistic block in the book.

I was acquainted with Jill decades ago here in Victoria, before she moved to Vancouver and then Toronto to study creative writing. I knew her to be smart, hilarious and a badass, both a boxer and a bouncer at a club downtown. She’s also been a tarot card reader, a tea-leaf reader, and a Christmastime Gingerbread Man mascot back in the day. My last memory of encountering her before she left Victoria was many years ago at a party at Carolyn Mark’s house. We were in the front vestibule and Jill was holding forth on merkins—I’d never heard the term before that night. Much hilarity ensued. There was a third person there—I think it was Panos Cosmatos—and he expressed irritation that the talk of merkins was going on too long. Or something along those lines.

Luckily for me, Jill moved back from Toronto in 2016 and has been a positive influence on me ever since. I’ve taken her three-month Creative Work program, participated in her Follow-Through Sessions, and have had several one-on-one consultations with her when I’ve been in a twist and need straightening out. I wanted to interview her because she’s the bomb, and because the services she offers are as well.

Please enjoy this meaty introduction to Jill’s brand of justice-based creative self-help.

THE INTERVIEW

(Note: All bolding is mine – ed.)

1 | Tell us the story of your business — its inception and evolution.

First off, thank you for inviting me to do this interview. I’m a big fan of both you and your work, and I love our friendship and how we connect on the topic of creativity (and make monkey noises when we greet each other).

The business started in January of 2017 as a partnership with my sweet fella, Andrew. It was called GOOD, and we ran it out of our live/work studio on the edge of Victoria’s Chinatown.

Andrew and I were both recovering from significant creative wounds. He had been a playwright who left the theatre world, and I had quit my MFA program after two years. GOOD was our way of crafting something different, a corrective to support other creators in ways we hadn’t been supported.

We knew from the start that the business would be iterative, evolving as we figured out what worked. We started with the idea of folks gathering around a 12-foot table (with tea and cake). We offered a range of programs, but over time the core offerings became co-working sessions, accountability groups, and a three-month program called Creative Work, which helped people figure out what creative practice could look like for them.

Then, the pandemic came, and the business was forced to shut down, and in 2021, we moved out of our downtown studio. The loss of the space—and the ability to gather in person—was a massive challenge but also an opportunity to reimagine what I wanted to create moving forward on my own.

In this next phase, I chose to work exclusively online and to focus on serving women, non-binary, and gender nonconforming folks. I renamed the business The Creative Good and leaned more intentionally into anti-oppressive frameworks. It was a way of realigning with my values and deepening the kind of impact I wanted to make.

What I offer—whether through my groups or one-on-one work—might best be described as creative self-help. But not the kind that positions the individual as a problem that needs fixing. I can’t stand that narrative. Instead, my work centres on what I call justice-based creative self-help, which says that the systems of oppression need fixing more than we do.

Foregrounding a liberatory view is essential to me. First, I don’t want our creative practices to reproduce the toxic conditions of productivity/hustle culture as demanded by late-stage capitalism. Second, what bell hooks called “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” is woven so deeply into our conditioning that naming it is crucial so that we can then decondition ourselves and reclaim our creativity.

2 | I’m resisting the urge to make a monkey noise at this juncture.

Please tell us about the next big change you’re making to the business, and what compelled you to make it. I know a smidgen of what you have up your sleeve and felt excited about it, which was the inspiration for this interview.

The monkey noises are bouncing around in my head too!

Over this past summer, I decided it was time to re-articulate my methodology. One of my teachers, Kelly Diels, describes a person’s methodology as being like Mary Poppins’ carpet bag—it’s the place where we pull our unique magic from. So, it’s not as dull as it sounds—it’s very jammy. She also explains that our methodology is “composed of our lineage, our learnings, evidence, research, and all the things we've studied and integrated so deeply they become almost automatic.”

My methodology forms the foundation of everything I offer and continues to grow alongside me. It’s important to me that it truly disrupts productivity culture—that is, the expectation that we should constantly work and produce—and is as liberatory as possible, so I felt like it was time to reconsider it.

The newest version of my methodology is framed as Invitations for Practicing Creativity. When I shared some of these invitations with you, I remember you being particularly interested in the first one: Embrace a relational approach to practicing creativity.

3 | Yes. Indeed I was. If I have this right, a relational approach involves a lot more self-compassion. Rather than cracking the whip, we “start where we are every day” and ask ourselves what we’re open and available to. We trust what comes up for us, so it seems safe to say it’s a more intuitive approach as well.

This definitely speaks to me. It seems that the last few years—whether it’s aging or the chaos in the world or both—my state of mind isn’t as stable and predictable as it once was. Trying to re-establish a consistent studio practice has been so frustrating—I get knocked off my horse so easily. Then come the self-recriminations. I have the impression that your new methodology gives plenty of room for less than robust productivity.

First, I want to give credit to Maria Bowler, a creativity coach I follow on Instagram. I signed up for one of her workshops and found that our thinking aligned closely, with significant overlap in the way we approach creative practice. After watching one of her videos, I was inspired to riff on and expand her ideas. This encounter was a key inspiration for re-articulating my methodology.

In considering creative practice, Maria highlights the difference between what she terms a “subject/object orientation”—or what I call a “transactional approach”— and a “relational approach”. In the subject/object or transactional model, we see ourselves as “doers of tasks,” a view that’s deeply tied to capitalism and productivity culture. In contrast, the relational approach invites us to see ourselves as being in nourishing, compassionate partnerships with our creative selves and the world around us. This idea resonated so deeply that I knew it had to be the starting point for my methodology. Although I was already teaching this concept, Maria’s insights gave me new language to communicate it more effectively.

One of the most beautiful questions Maria poses—and you echoed here—was a version of: What am I open and available to right now? In a transactional approach, this question has no place. The focus is on rigid adherence to external expectations and “shoulds.” The relational approach, on the other hand, meets us where we are, right in the present moment.

At its heart, a relational approach is about shifting from doing to being. You brought up consistency earlier, and Maria emphasizes that in this model, consistency doesn’t stem from what we do but from who we are. Even if you’re not regularly entering your studio, you haven’t stopped being a creative person and your creativity hasn’t left you.

It’s occurred to me that, in many ways, creative practice mirrors spiritual practice. Spiritual practice isn’t about checking off items on a list; it’s about deepening your relationship with what you hold sacred. Similarly, creative practice isn’t defined by output; it’s about your relationship with creativity itself, your perception of the world, and the way you move through it.

4 | Whoa—I love that you are likening creative practice to spiritual practice, though to me the word “sacred” smacks more of religion than spirituality, per se. Topic for a separate interview, perhaps? (Insert monkey sounds).

I do see what you’re saying. As you know, a couple of years ago I was jolted off course quite abruptly by some life events and have been struggling to regain a solid creative practice ever since. I’m finally at a point where I feel ready to start work on a graphic memoir that I completed the writing for two years ago, but I’m so rusty in the drawing and painting department. I know very well that I need loads of time to play around in my sketchbook and get comfortable again, but I resist it! Nothing could be harder for me to do! And what could possibly be causing that resistance, if not the engrained beliefs that I must produce something if I’m going to spend time in the studio?

Produce something sellable? Produce something admirable? I’m not sure, but messing around aimlessly in my sketchbook does not fit the bill, or come easily.

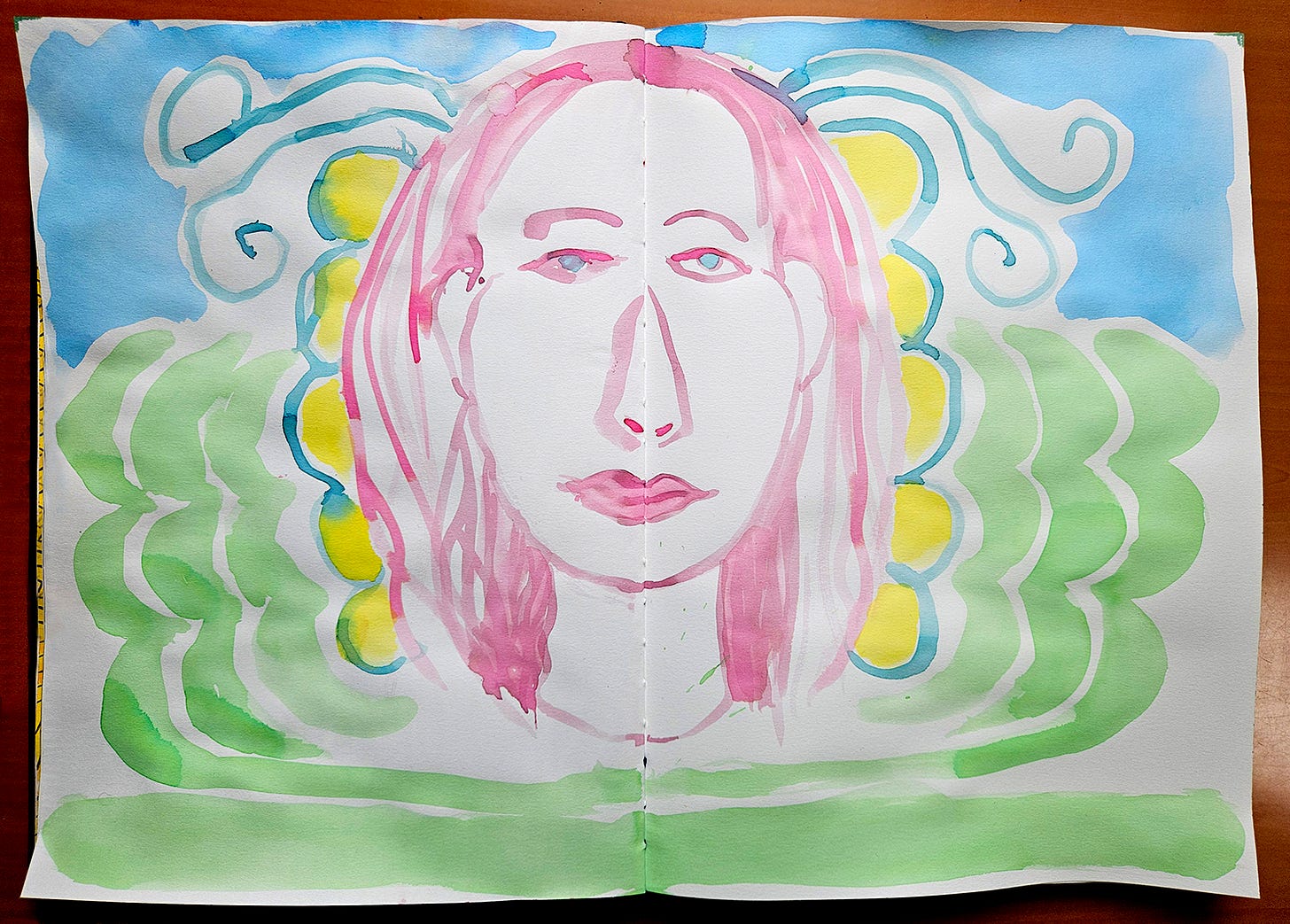

So today, I forced myself to play in my sketchbook. I used the method where I hold a brush in each hand and paint the left and right sides of the image simultaneously, which is meditative and helps me bypass the need for control or for making something “good”.

I did that for less than an hour. I became calm. I felt like myself again. I was reminded—why I need to be reminded repeatedly I don’t know—that this is my lifeblood.

I was also reminded, to return to the topic of spirituality, of a moment in art school back in the eighties when I was working on a painting and I had an epiphany. “Oh,” I suddenly realized, “This is God”. Yet here I am thirty-five years later, still fighting the compulsion to generate products and “check things off a list”. I’ll get it sooner or later, haha.

NEXT QUESTION! In light of your refreshed methodology, and the experience you’ve gained helping writers, artists and musicians for years now, what has this work taught you about the things creative people struggle with the most? What seems to help them the most?

I’m so glad you had that experience. I’ve always believed that creative practice has the power to bring us home to ourselves. It makes us remember who we are.

Before answering your question, I want to mention another one of my seven invitations: Locate yourself within your creative growth phase. This concept is broken down into three phases where you might be at present: Roots, Shoots, and Blooms. I love these metaphors because they highlight that we’re more like gardens than machines, each phase nurturing our growth at its own pace. Right now, you’re in a Roots Phase—a time for grounding yourself in your creativity, perfect for re-establishing your practice after an extended break, and building confidence by simply practicing painting.

The great thing about locating yourself within your Creative Growth Phase is that it also acts as a framework for all your activities. So, for example, if you’re in a Roots Phase you don’t need to focus on having a finished work to offer to the public (as you would in the Blooms Phase). Instead, you can be playing and experimenting to just get things moving again. You can do this quietly behind the scenes until you’re ready to move on to the Shoots Phase and grow your body of work.

Now, your excellent question. In my experience, the most common struggles creators face boil down to three main areas: internalizing productivity culture, not having systems to support their work, and mindset challenges like perfectionism, imposter syndrome, and fear of being visible. So, let’s unpack these a bit.

First, productivity culture can really mess with creative people. It shows up as guilt or shame when our creative time doesn’t produce something tangible, or as a constant push to prioritize output over the joy of the process—which often leads to burnout or creative blocks. There’s also this pressure to justify creativity by how useful, profitable, or well-received it is, which can make it hard to embrace play. Many of us struggle to carve out time and energy for creativity, especially if we’re working full-time jobs, caregiving, dealing with chronic health issues, or any big life things. For instance, you might find yourself staring at a blank page, knowing you have a limited window to create, but feeling unable to start due to the pressure to “make it count.”

The shift that helps here is adopting the relational approach to practicing creativity, which we’ve already talked about. Instead of focusing on the product or outcome, this fundamental shift encourages you to value the process itself. It’s about seeing creativity as part of who you are, not something that needs to prove its worth. A relational approach also reminds us that creativity doesn’t require huge blocks of uninterrupted time. Even brief moments of play or experimentation count—and they don’t need to justify themselves. We don’t have to move at the speed of capitalism, which is inherently exploitative. This approach can transform how you feel about your creative practice, bringing more joy and reducing stress, even when the outcome isn’t what you hoped.

Then there’s the lack of systems. Without a clear structure—and basic project management skills—it’s easy to feel paralyzed or stuck, which leads to inconsistency and frustration. I like to say, “Inspiration doesn’t get things done, habits do.” This is where a system comes in—a collection of habits designed to support your activities and projects. A good system is like a safety net, catching you even on low days. And a “systems-first mentality” allows you to feel satisfied not just when you achieve a goal, but when your system is steadily supporting your practice too.

Finally, let’s talk about mindset challenges. Perfectionism is a big one, so I’ll use it as an example. It’s likely that if you’re not part of what Audre Lorde called “the mythical norm”—a narrow set of characteristics which usually includes being male, white, thin, young, able-bodied, heterosexual, cisgendered, and financially secure—you’ve been taught that perfectionism is the price of entry. So, perfectionism is often used as a gatekeeping tool. That pressure often leads to anxiety, procrastination, or overworking because we’re so scared to share something that isn’t “perfect.”

The solution here is about flipping perfectionism on its head. Rather than aiming for “good enough,” which is the usual advice, but feels reductive to me, I encourage embracing deliberate imperfection in a way that means allowing a piece to be done when it feels honest, true to itself, and coherent. Perfectionism suffocates creativity, while deliberate imperfection lets a piece breathe, retain its humanness, and connect more deeply with others. It’s not about settling; it’s about freeing yourself from all the beaty-uppy feelings that come from striving for an impossible ideal. It’s a stand against the belief that perfection is a prerequisite for worthiness.

5 | Thank you, your answer is so great. Exhaustive, and very helpful. You know you need to write a book illuminating your methodology, right? I know, I know—you’re working on your first novel and trying to run a business, so who’s got the time? A gal can hope.

Placing myself in the Roots Phase of my creative life is calming. It gives me permission to cool my jets and relax. So, thank you for that.

Okay, last question! This might be tough to answer, considering how creative people struggle in so many ways. But here goes. To borrow from Tim Ferriss, what message or piece of advice would you put on a billboard to reach the millions of people out there endeavoring to maintain a creative practice? Whatever speaks to your heart.

You’re so welcome—it’s been a pleasure. And yes, I absolutely know I need to write that book. I’m aiming to start work on it in 2026.

That is a tough question!

Every creator has their own struggles, but I want them to remember that their art, their joy, and their voice matter—especially now. We’re facing so much: fascism, genocide, climate destruction, and more. Even in the face of these challenges, I believe in our incredible capacity to create. Making things and embracing joy are acts of resistance with profound power. This isn’t just about self-liberation; it’s about collective liberation.

So, given all we’ve discussed, my billboard would simply say:

Shine your damn light anyway.

Thank you Jill—I swear that’s the best billboard message I could imagine you giving. I’d also like to thank you for your fabulous answers to my questions. Your Mary Poppins’ carpet bag is rich and nourishing and leaves no stone unturned, and I hope we’ve given readers a sufficient taste of it here.

MORE FROM JILL:

JOIN JILL’S WINTER FOLLOW-THROUGH SESSIONS

Now open for intake, these quarterly sessions are designed to provide a full season of accountability, encouragement, and support for creators. Hosted on Zoom, every second Monday from 6:30 pm to 8:30 pm PST, the winter sessions will run from January 6th to March 31st.

This offering includes:

Seven live group sessions

Weekly check-ins in a private Facebook group

A spiral-bound workbook and planner

A one-hour, one-on-one Shine Session with Jill

There are only eight spots available. For details please visit www.thecreativegood.ca/follow-through-sessions.

DOWNLOAD THE SEASONAL CREATOR WINTER WORKBOOK

Attune your creative practice to the energies of winter with this 12-page downloadable PDF workbook. Designed to be printed and filled in by hand on or around the Winter Solstice (December 21st, 2024), it’s a perfect tool to prepare for the shift of seasons. Inside, you’ll find:

Introduction

Attuning Your Creative Practice to the Energies of the Season (reasons and benefits)

The Energies of Winter (what’s happening in nature and metaphors you can draw on)

Winter’s Shadow (what to look out for)

Energetically-Aligned Kinds of Creative Work for Winter (five specific ways you may choose to focus your attention)

Reflection Prompts (15 questions to get you ready for winter)

Get the winter workbook here: www.thecreativegood.ca/the-seasonal-creator-workbooks

🪞Thank you very much for being here.

🪞If you find value in my posts, please consider supporting me and my work by becoming a paid or free subscriber:

🪞Or please click on the little heart, leave a comment, or share this post.

🪞Buy TAKING NOTE: Creating Ourselves Through Journaling—$42 CAD. More info here.

🪞Check out my resource page where I’ve started compiling things related to journaling, note-taking, and more.

🪞Buy my Collage Class—$40 CAD for a 1-hour download. More info here.

🪞Visit balampman.com

🪞There's always Instagram

Jill is an articulate intelligent communicator and this interview of course shows that. Lots to sink one's teeth into.

I love a lot of things in this newsletter but I PARTICULARLY love the re-framing of consistency to be defined by who we are and not what we do.