Welcome to the latest issue of Feed the Monster: a monthly art journal for creative, curious, imperfect and sometimes disheveled humans.

Click on the ❤️🔥 above if you want to help this publication be seen, and grow!

You can read more about FTM here. If you like it, please consider subscribing.

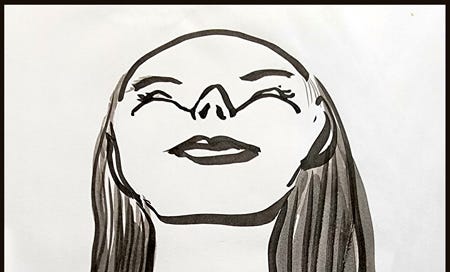

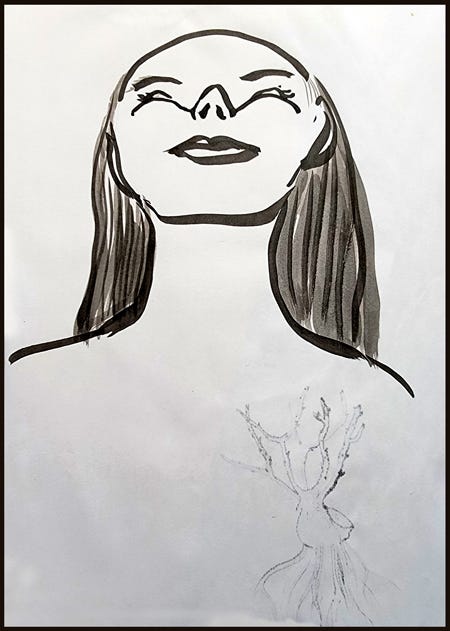

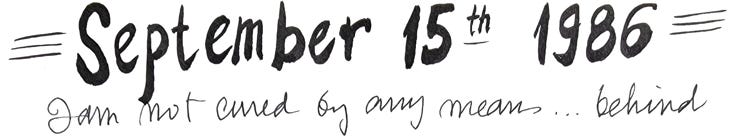

I’ve always used ink in my journals when it felt called for, though I didn’t start painting with it in earnest until 2015. I’d use it to herald the start of a new journal or a new chapter in my life:

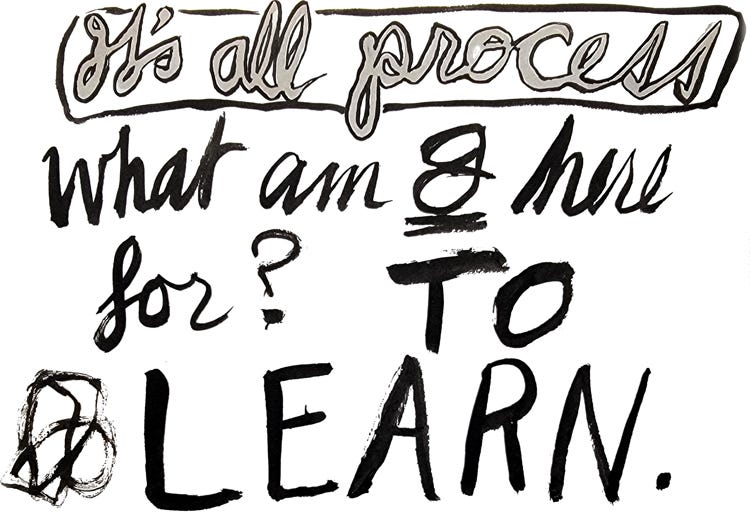

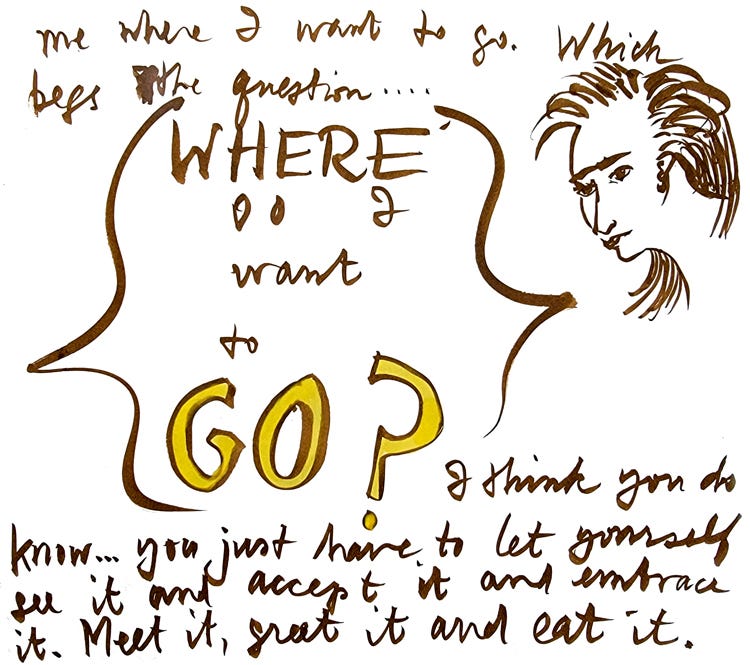

…or to boldly declare something (to myself). Such as this outburst from 2006:

I wouldn’t use it for my regular writing bouts—it takes too long to write with ink and brush. Journal writing needs to be done quickly and without hesitation in my opinion, lest you start to think about what you’re committing to paper. I’d use it for emphasis, though I was the only person these things were being emphasized for. Again from 2006:

Or sometimes I might give myself a pep talk:

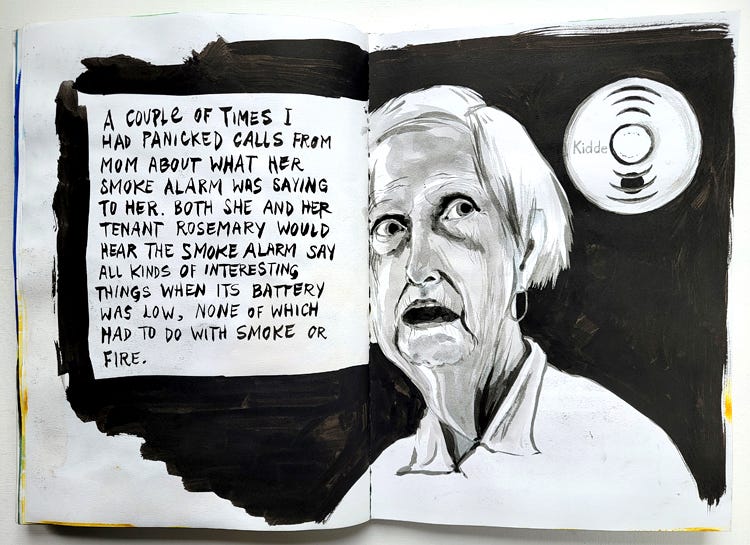

When I started experimenting with graphic memoir pieces in ink for my Life’s Work project last year, I tried various ways of rendering the text. First I tried handwriting with a brush-pen. Then I tried handwriting with a dip pen and ink, first lower case and then upper case. None of that felt right.

Finally in July when I started painting the words and images together in my sketchbook, things started falling into place a little more. I decided to stick with writing in upper case and went back to the brush-pen—a pen that has a brush tip, and a constant ink supply…

…but soon switched to using an actual brush and a bottle of ink. Specifically, a bamboo brush, which I’ve mentioned I was using in order to have less control when painting. But in this case a bamboo brush is appropriate, as this is what’s used for Chinese calligraphy, for example. Not that that’s what I’m doing. But I am using it to form letters.

Using ink and an actual brush felt better, felt right. There’s more subtle variation to the letters, giving them more character. And the hand of the writer is more present and felt. To use the same instrument for the writing and the artwork felt felicitous. The dipping of the brush into the ink bottle, the return of the hand to the page, the act of forming the letters with the brush. It didn’t feel so different from drawing the artwork. It was writing, but it wasn’t. As Lynda Barry says,

“A kid learning to write the alphabet is actually learning to draw the alphabet. When I remind people that writing by hand is actually drawing, they look surprised and then try to figure out how it is not drawing, how it is different, but there is no way to argue it.”

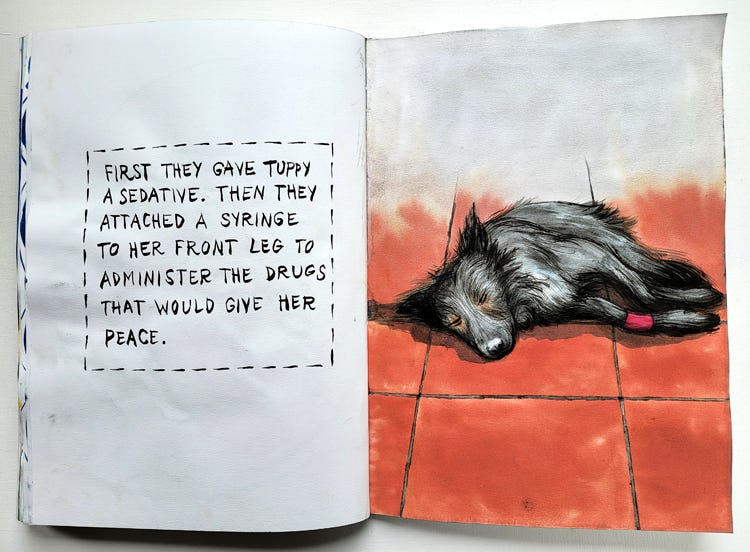

Bringing artwork and writing together these last three years with Feed the Monster has brought a certain special satisfaction for me. In the same way and perhaps moreso, the writing and drawing in ink in my sketchbook for Life’s Work has proven to be a fortuitous and alchemical learning experience—a culmination of years of obsessions and interests. If it wasn’t clear before, getting to this point with Life’s Work clarified for me what the way forward is going to look like.

For now.

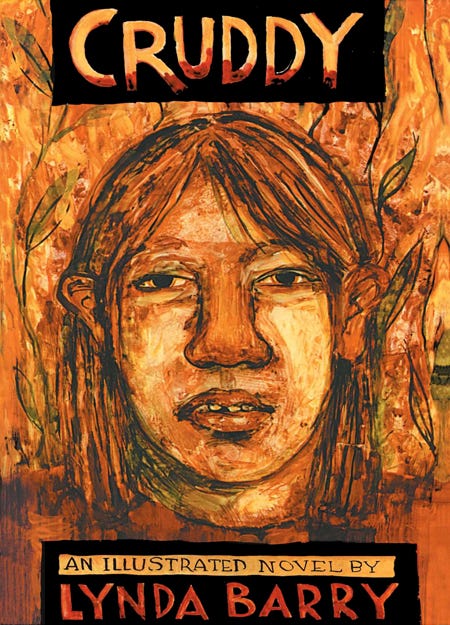

I discovered that when Lynda Barry was experiencing writer’s block with her illustrated novel Cruddy, she decided to try painting out the words in ink instead of typing them. I found this incredibly exciting—mostly because, who does that? And how did that go? I read the book years ago, but wasn’t aware of how it’d been written.

“Writing Cruddy was one of the most exhilarating experiences once I finally gave up on trying to write it on a computer and trying to make it meaningful to others.

Once I decided to write it in the slowest possible way– which is with a paintbrush— the novel came so fast it was like watching a movie. I felt like the next word was always waiting for me after I finished the one before it.

The trick seemed to be the very slowness of the process. I found that if I just concentrated on the sentence I was writing and didn’t try to think of what the next one would be, it seemed to be there anyway, like the way the ground is there for you when you take a walk.”

“When I was working on Cruddy, I didn’t really edit anything out based on the content– because I was writing it with a paintbrush rather than a computer I couldn’t delete anything as I wrote it so it stayed and had a chance to present itself in my mind for a much longer time than sentences typed on a keyboard. It didn’t allow me to delete the things in the story I didn’t yet understand.

I believe a different kind of writing comes from writing by hand slowly. Cruddy really taught me that.”

Most of the text I was painting in ink in my sketchbook for Life’s Work had already been written on the computer—I was really only transcribing it—so I can’t claim to have used Barry’s method. But the writing did change as I rewrote it with brush and ink. If nothing else, writing this way encourages economy.

“The paintbrush itself is the best editor I ever had. I know I am going to have to paint each letter of each word and that alone acts to cut down words. Even if I’m in a groove and getting fast with the brush, it’s still too slow to go on about things for long.”

I’m going to be quoting Lynda Barry a lot here, because she describes what I was trying to get at in my No Thinking Allowed post a couple of months ago so much better than I ever could. The act of tuning out pesky thoughts and letting a different part of your brain take over. The part that actually knows what it’s doing.

“Writing this way gave me a feeling I remember having when I was a kid and cutting things out of construction paper for a shoebox diorama or coloring in a coloring book when it was going really well, or making tiny channels and rivers between dammed up mud puddles in the alley, it gave me that same feeling, that sensation of being absorbed in the physical act of what I’m doing in such a way that the back of the mind had a chance to come forward and move things around.”

You can bring your intellect to bear, and of course you most certainly should—but that can come later. The intellect is not the only player. We’re taught in Western culture that it reigns supreme… that nothing else is to be taken seriously. That the body is primarily there to transport your brain around, like a sultan is carried around in a sedan chair. But the body has its own wisdom, and there’s power in using your hands.

“I did know that the brush itself and the act of writing with a brush changed the content of the work immediately– suddenly I was writing an entirely different story from the one I planned to write and one I’d been trying to write for ten years on a computer.”

According to D.B. Dowd, author of Stick Figures: Drawing as Human Practice:

“I think there is an important distinction to be made between the digital and the manual. We are physical creatures. Our hands are still fixed at the ends of our arms, which is, in fact, a big deal: our brains exploded in size when our hands gained functionality through opposable thumbs. The sheer number of nerve endings in our fingers connects learning to touch and manipulation.”

What came out in the writing surprised Barry, because Cruddy is astonishingly dark and violent. It’s also beautiful and hilarious. It’s a story told by a teen who lives in an exceptionally cruddy world. I decided to reread it once I’d started this post about Barry’s method of writing it. At first I was repelled—a big part of me resists indulging in any more darkness than I have to these days. But I kept going back to it… I couldn’t stop. Initially I would spell it off with the Zadie Smith essays I was also in the middle of, but soon I just gave in to Cruddy and put aside the essays. It has a powerful draw. As The New York Times states on the cover: “A work of terrible beauty”.

Barry one last time:

“The hands are the original wifi devices. They are astonishing things, and there are some theories that our hands have quite a lot to do with the development of our human brains in terms of evolution.

Watch people when they talk. They move their hands. When we write by hand there is a kind of movement in it, that, at least for me, makes all the difference in terms of content.”

It’s all cave paintings. And, uh, we are the cave people.

Or are we apes?

Either way, I’m going to keep making ink marks with my hands.

Most of the Lynda Barry quotes used here are from an interview with Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer.

HEY! It helps me broaden my audience if you like, share, or comment on FEED THE MONSTER. Or tell just one person about it! Word of mouth is how work like this gets noticed and sustained. Thank you.

If you’d like to receive Feed the Monster by email once a month, please do…

Buy my book 100 Days of The Artist is Present

Take my Collage Class

Visit balampman.com

There's always Instagram

I find the discussion around techniques and thought processes, physical vs mental, different tools all fascinating and relevant to me. Plus I think "Keep Up The Good Work Asshole" should be made into a T-shirt. That shit sells.

I second the t-shirt! This was really fascinating BA. I love the fact that writing IS drawing. Had never thought about it that way. Actually, all your Feed The Monsters leave me with a new spin on most everything…thank you😊. (It’s probably frowned on to use emojis…but damn…emoji it is)